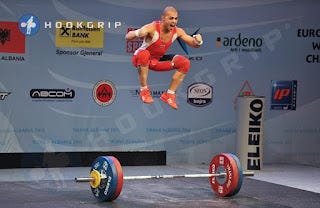

A plyometric movement is a quick, explosive movement using the spring-like action of the tendons, so we typically associate plyometrics (“plyos”) with a series of jumping, hopping, and bounding exercises, like squat-jumps, burpees, box jumps, and single-leg hops back-and-forth over a line, etc. The goal of plyos is to increase muscular power (as differentiated from muscular strength), as well as to increase the resilience of the joints, tendons, and ligaments in the legs. In terms of athletic performance, the difference between strength and power is the speed of the movement, with powerful movements being performed more quickly. For example, jumping rope and sprinting can both be considered plyometric exercises, with jumping rope being a great option as an extended warm-up prior to a strength training (ST) workout or a high-intensity run workout.

Power has been associated with improvements in running economy (RE). Studies have appeared in the scientific literature demonstrating that eliminating portions of endurance training in favor of explosive activities, or adding plyos to an existing running program for several weeks, can improve RE and performances in short-distance racing without needing to see an accompanying change in VO2-max! These benefits are evident regardless of ability, gender or age.

These results are best understood in that any time a muscle group becomes stronger and more powerful, fewer muscle fibers are recruited to perform the given task, thus allowing the muscle group to have more fibers in reserve for continued work (i.e., “neuromuscular efficiency”). Basically, this means that less energy is used to cover the same distance. Therefore, it has been shown that power training, not just ST, will lead to enhancements in RE. Of course there is no substitute for running if one wants to run faster and farther; however, during off-season training, when a major goal for most athletes is to introduce new types of training, or during peak racing season, as the run volume gradually decreases, plyos are another option for high-intensity workouts (in addition to speed workouts, obviously).

A plyos workout is typically done 1-2x per week and is based on the total number of foot contacts, or “touches.” For beginners, the recommended range is between 60 - 100 touches per session for a few weeks, before progressing toward 100 touches for a few more weeks, and then possibly beyond (capping the total touches at ~140). Reps can be performed as double-leg exercises where both feet jump, or contact the ground, simultaneously, or as single-leg exercises, although most (but not all) single-leg plyos should be reserved for experienced athletes. Sometimes additional equipment can be used to add variety and difficulty into these workouts, like small hurdles and boxes.

Plyos are a great compliment to ST and can even be done as a warm-up on lower-body ST days, but don’t underestimate how strenuous these exercises can be! For many of the exercises, it’s not necessarily the muscles that are the target for strengthening; rather, it’s the joints, tendons and ligaments, which are often a limiting factor on courses that have many downhills (e.g., Boston Marathon). Hence, plyos are a terrible idea if you haven’t been pain/injury-free for at least 8 weeks in a row! With that said, plyos usually are not “muscle-burning” workouts, and the goal isn’t to feel exhausted at the end. Muscle power and muscle exhaustion are on two different sides of the spectrum, so don’t mistakenly take the wrong mentality into a plyos workout. This is why the rest between sets within a plyos workout is “full recovery”, which means there is no fatigue in the muscle prior to each set, which allows for each set to be performed with maximum power! Additionally, before starting any plyos training, I recommend completing at least 6 weeks of general ST in order to strengthen/prepare the joints, tendons, and ligaments, as they incur high levels of stress/impact when performing various jumps and hops.

I recommend plyos as long as an athlete is familiar/comfortable with jumping exercises in general, but technique is paramount, especially in terms of the landing mechanics, which brings the conversation back to the joints, tendons, and ligaments once again. You will often see coaches/trainers doing plyos with athletes, yet there is little to no emphasis on the proper landing mechanics, and this lack of proper focal points can lead to injury. Therefore, do not do plyos unless there is 100% certainty on the landing mechanics for each exercise. Similar to how I frame a discussion on proper ST technique, if you couldn’t teach jumping and landing mechanics to a small group, then your plyos form probably isn’t ideal.

Train Smarter, Not Harder!

Mike